This post explores the motivation and design behind the loose coupling between our actors and capabilities.

Developers have a number of creeds to which we hold dear. Sometimes these show up as pattern and practice recommendations. Sometimes they appear in blog posts, conference talks, or streams. They can also appear indirectly via the code we write. One such creed is the tenet of loose coupling. Everything needs to be loosely coupled, because we all known and preach that tight coupling is objectively bad. Everyone seems to know this, but we rarely stop to think about why.

Before getting into the meat of this post, let's take a second to define non-functional requirements, often abbreviated as NFRs. The core, so-called "pure" functional part of our business logic defines the what of the application, while the NFRs define the how.

By way of example, let's examine the anatomy of a fairly commonplace microservice that you might see deployed in any enterprise in a cloud or on Kubernetes. This example service is a RESTful one that validates requests, reads and write bank account information from a data store, and responds accordingly with JSON payloads over HTTP. For this sample, we might have the following sets of functional and non-functional requirements.

Functional Requirements:

- Allow for the creation, deletion, and update of a bank account

- Allow for querying summaries of multiple accounts

- Allow for querying details on a single account

- Validate all requests according to business rules

- Accept requests via HTTP

Non-Functional Requirements:

- Store account details information in Postgres

- Store account summaries in an in-memory Redis cache

- Emit logs to stdout

- Run 2 instances of the service per availability zone

- Secure access to the HTTP endpoint via reverse proxy

- Emit open telemetry spans and traces

- Support and expose a prometheus metrics endpoint

- Use (your favorite) HTTP server library

- Use (your favorite) SSL tools

- Secure access to the service via bearer token

The amount of work required is definitely skewed toward the NFR end of the scale. With most of today's traditional development tools and ecosystems, every deployment artifact bundles the solution to functional requirements with just one of the many solutions to the non-functional requirements at build time.

It's pretty routine for developers to build a service that only works with Redis, only works with Postgres, only supports one way of emitting traces and spans, only manages logs one way, only handles prometheus metrics one way, only secures things one way, ... you get the idea. We might have some clever abstractions in our library code, we might even deftly employ anti-corruption layers, but in the end, we own our dependencies, and despite calling it a microservice, we're shipping a brittle monolith that only works against one rigid target environment.

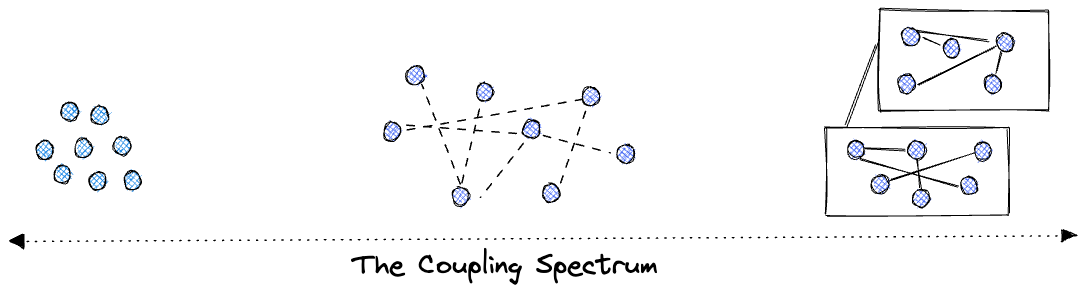

Like everything in our line of work, there are tradeoffs. There are some advantages to making fixed architecture decisions once and codifying those decisions into the deployment artifact. This can often buy you rapid time to market and simplicity in some areas, while dramatically increasing complexity in others. The reverse is true as well, if everything is too flexible, too loosely coupled, then this mess may be too difficult to manage.

As illustrated, there is a spectrum of coupling from utter and total tight coupling to free and unfettered, uncoupled design. On the far right, all of our components are stuck together, then crammed into a box and sealed. On the far left, we can end up with thousands of little tiny pieces that are so flexible that maintenance and discovery is a nightmare. Without me saying it, I bet you can imagine examples of current technologies that sit on either end of this spectrum.

What we want, rather than extremes, is the right balance. I want to write just the code that satisfies my functional requirements, and then let other aspects of my system take care of satisfying the NFRs. To satisfy the above example, I want to write code that utilizes some key-value store, some SQL database, some web server. I can then run that component against a test environment on my laptop, a medium-sized environment in the CI tests, and then massive scale when in production. More importantly, while in production, I can even change the deployment shape to suit changes in my user base, demand, load, etc.

When we separate the functional and non-functional requirements across specific contracts, then we can hopefully achieve the right balance between coupling. You might look at the word contract here and think we're just going back to anti-corruption layers or abstraction libraries inside our code. The difference is subtle but vital: requiring that the thing that satisfies the contract not be a part of your code is the magic sauce that balances the coupling scales.

If we own our dependencies, and the implementation of a contract is not a tightly coupled dependency, then we can finally say that, as developers, we don't own the non-functional requirements. NFRs are still mandatory, still important, and still have to be dealt with. However, if our unit of deployment doesn't own them, then they are free to change, update, and move on their own cadence, for their own reasons.

wasmCloud, NFRs, and Capabilities

All of this lead-up and background hopefully explains why wasmCloud has chosen the abstractions we've chosen. We know that if we write a microservice that requires access to an S3 bucket, it's going to be a huge pain to work with locally (even with tools like minio). The functional requirements of my code are "store this data in a blob store". Why should we be forced to decide on S3 and then live with that decision for the lifetime of the component?

By implementing a contract like the one we have for wasmcloud:blobstore, and writing code against that contract, wasmCloud actors can interact with files on disk during the local developer iteration cycle, some other abstraction during automated tests, and then real S3 buckets in production. The important thing is that the code no longer owns the choice of S3, or the configuration thereof.

WebAssembly's enforced hard boundary between the guest and the host mandates that developers choose where their code ends and the host-provided functionality begins. By forcing us to draw this line for real rather than have this line be something that is either implicitly or accidentally drawn (and subsequently violated), we can actually turn this so-called limitation into an advantage and build highly composable, distributed components that have just the right amount of coupling with the components that satisfy their non-functional requirements.

To see how wasmCloud has leveraged this kind of NFR decoupling, check out our documentation on capability providers. For an example of us demonstrating hot-swapping between a file system and S3 live, at runtime, without a recompile or redeploy, check out this wasmCloud community meeting.

Today wasmCloud uses the Smithy DSL to define and describe these contracts. When we started, we had to fend for ourselves when it came to contracts and code generation. Hopefully soon, when the component model becomes more of a real thing, we'll be able to take our contracts and turn them into component specifications that will work in wasmCloud or anywhere else that supports components.

That is the real pot of gold at the end of the rainbow, and the ultimate payoff for maintaining the right coupling balance.

Cover Photo by Daniel Schwen - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4784168